Colossus Brass Band: Sing On

Unabridged Liner Notes by Ricky Riccardi

The history of brass bands in New Orleans is so rich that all one has to say is a word or two and an entire sound can be conjured up. Tuxedo. Eureka. Olympia. Dirty Dozen. Rebirth. Hot 8.

Now entering the canon with their debut album Sing On is a new brass band whose very name alone speaks volumes: the Colossus Brass Band.

The dictionary definition of “colossus” refers to “a person or thing of enormous size, importance, or ability.” If that’s the case, the Colossus Brass Band is a good example of truth in advertising. This just might be the greatest assemblage of talent on a single New Orleans brass band record. The music truly speaks for itself, but a few words should be said about the artists on Sing On and how they came together to create a true Murderer’s Row of a band.

Mentorship has been ingrained in the development of this music ever since Joe Oliver took young Louis Armstrong under his wing 110 years ago. It quickly became clear that for this music to survive, it would have to continue being passed down to the generation that followed. Sing On is just not the name of an old hymn; it was chosen as the name of this album because the music continues to sing on brightly with the arrival of each new generation.

This project is the brainchild of trumpeter Mark Braud, a musician whose New Orleans roots run deep through his bloodline. There’s his surname, “Braud,” which conjures up the spirit of Duke Ellington’s longtime bassist, Wellman Braud. His grandmother was Nazimova “Chinee” Santiago, sister of pianists Lester and Burnell Santiago. And his grandfather was trumpeter/pianist/composer John “Pickey” Brunious Sr., father to Mark’s trumpet-playing uncles John Brunious Jr. and Wendell Brunious. In a city overflowing with trumpet players, Wendell quickly rose to the upper echelon with a style of his own that effortlessly combined the drama and fire of Louis Armstrong’s style with the clean phrasing and hip harmonic knowledge of a Clifford Brown, making him one of the most influential trumpeters of his time. It was almost predestined that Mark would follow a musical path, but Uncle Wendell made it easier for him by gifting him a trumpet when Mark was 12.

This was the mid-1980s, a time when New Orleans traditional jazz was a bit in flux. In the 1960s, there was a revival of interest in this music due to the popularity of Preservation Hall, a new venue dedicated to showcasing the pioneers of jazz, many of whom were born at the turn of the 20th century. It was something of a novelty to see these old men and women spring to life on the bandstand--but what would happen to the music when they departed?

Enter Danny Barker. Born in 1909, the guitarist/banjoist/vocalist/recounter left home as a young man and a had a successful career up north playing with the likes of Cab Calloway, Charlie Parker, and Henry “Red” Allen. But when Barker returned to New Orleans in 1965, he was dismayed at the lack of young African Americans playing traditional New Orleans music. He took it upon himself to start the Fairview Baptist Church Marching Band, dedicated to teaching young, primarily Black musicians the traditional jazz repertoire, letting them know that this was their music and it was up to them to keep it alive. Barker mentored future stalwarts of the music such as Leroy Jones, Lucien Barbarin, Dr. Michael White, Shannon Powell, and two musicians heard on Sing On, Kirk Joseph and Gregg Stafford. “That group saved jazz for a generation in New Orleans,” clarinetist Joe Torregano once said.

Thus, the New Orleans traditional jazz scene was alive and well in the 1980s and 90s as musicians like Stafford and Wendell Brunious began taking their rightful places on the bandstand at Preservation Hall and other venues throughout the city. They were soon joined by other younger musicians such as Freddie Lonzo, who began playing trombone as a teenager, quickly gobbling up brass band experience with the likes of Harold Dejan’s Olympia Brass Band and trumpeter Ernest “Doc” Paulin’s Brass Band (Lonzo calls Paulin “the Danny Barker of Uptown”). He soon landed a job with drummer Bob French’s Storyville Jazz Band, which Lonzo compared to “like going to university,” and by the mid-1980s, he eventually found himself as a regular at Preservation Hall.

Lonzo shares trombone duties on Sing On with Craig Klein, another New Orleans native who, like Braud, has his life changed when he received a trombone from his uncle, trombonist Gerry Dallmann, when he was in third grade. Klein became transfixed by the music at Preservation Hall and soon befriended trombonist and Danny Barker acolyte Lucien Barbarin. It was Barbarin who recommended Klein for the job in pianist and vocalist Harry Connick Jr.’s big band, one of the other great incubators of New Orleans talent in recent decades. Klein remained for 16 years, all while serving as a founding member of two brass bands, The Storyville Stompers and The New Orleans Nightcrawlers, not to mention the popular slide-heavy ensemble, Bonerama.

Braud was far from the only musician of this next generation to have the music in his DNA. Reed specialist Roderick “Rev” Paulin, the son of the aforementioned trumpeter Ernest “Doc” Paulin, has 40 years of experience under his belt, making him a first call musician comfortable in all styles. The same can be said of drummer Gerald French, the nephew of the aforementioned drummer Bob French. Since 2011, Gerald has been entrusted with leadership of the Original Tuxedo Jazz Band, the oldest continuously performing jazz band in the world, in addition to his work with Charmaine Neville, the New Orleans Catahoulas and just about any other New Orleans musician or combination one can think of.

Then there’s sousaphonist Kirk Joseph--son of trombonist Waldren “Frog” Joseph--who, after his time with Danny Barker, became a founding member of the Dirty Dozen Brass Band in 1977, instigating a revival in brass band music in New Orleans that continues show no signs of slowing down today. The Dirty Dozen added funk and R&B sounds to the mix, while later groups like the New Birth Brass Band mixed in funk with hip hop. Tanio Hingle beats the bass drum for New Birth, but he shows his adaptability on Sing On with his rock solid bass drum work on ten selections. Hingle actually splits bass drum duties with trumpeter Gregg Stafford, making his bass drum recording debut on Sing On. Stafford has remained dedicated to the traditional brass band repertoire heavy on hymns and dirges and has led the Young Tuxedo Brass Band since 1984.

That just leaves the two youngest members of the Colossus Brass Band, long cornetist Kevin Louis and clarinetist Bruce Brackman, both of whom are in their late 40s. Louis began playing with brass bands in the 1990s but left home to study at Oberlin and performed for a number of years in New York City, which left him somewhat jaded. His return home rejuvenated his love for New Orleans traditional music, and he quickly sought out the mentorship of elders like Wendell Brunious to set him on his path to being one of the most respected young musicians on the scene. Louis brings a modernist sensibility to traditional music, yet like his elders, his playing is warm, personal and serves the music without any self-indulgent tendencies. Brackman also has a modern background, having studied with avant-garde clarinetist Alvin Battiste early on, but he soon became a fixture on the burgeoning Frenchman Street swing scene in the 2000s before eventually taking his place, often alongside Louis, at Preservation Hall.

This brings us back to Braud, who has had quite a career since Uncle Wendell first gave him that trumpet at the age of 12. Like Klein, he joined Harry Connick Jr.’s band in 2001 and still tours with them today. After the passing of his uncle John Brunious Jr. in 2008, he assumed leadership of the touring Preservation Hall Jazz Band until 2016. He continues to perform regularly at the Hall, most notably on Monday nights as a member of Preservation Brass, the Hall’s resident brass band, with Kevin Louis, Roderick Paulin, and Wendell Brunious often by his side.

Braud has amassed incredible experience in a wide variety of settings, but it’s clear as he approaches his early-50s that he now views himself as an important bearer of the tradition. While the brass band scene has incorporated so many different styles and sounds into its tapestry in recent years, Braud is serious about preserving the roots of the music, the reliance on dirges and hymns and celebratory statements, all delivered with passion, soul, and swing.

At the same time, Braud realizes the music should not be treated as a museum piece, something only belonging to the past. The music on Sing On speaks to today. There are traditional favorites like “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” and “When the Saints Go Marching In,” but Braud and frequent collaborator Meghan Swartz have stacked the set list with original songs that are just as catchy--if not moreso--than any of the old warhorses.

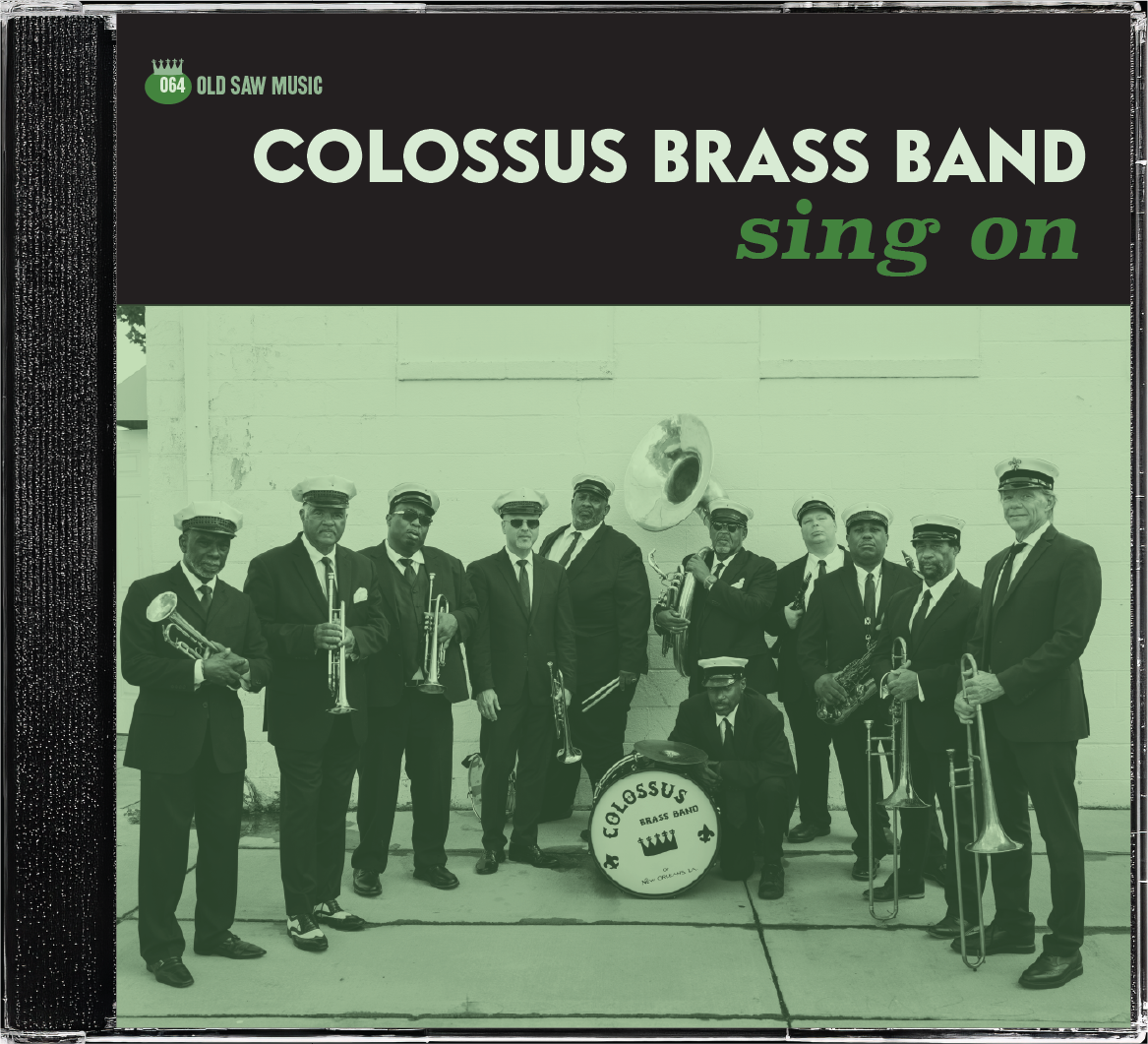

To accomplish his goal, Braud hired the cream of the New Orleans crop. On a personal note, I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw the all-star team Braud had assembled. A trumpet section with younger guard greats Braud and Kevin Louis paired with elder statesmen Wendell Brunious and Gregg Stafford? That alone makes Sing On one for the pantheon, but what about the delightful pairing of Craig Klein and Freddie Lonzo on tailgate trombones? The unbeatable team of Bruce Brackman and Roderick Paulin on reeds? New Orleans has always been a drumming city, and does it get any better than Gerald French on snare with Tanio Hingle and Gregg Stafford splitting bass drum duties? And holding it all down at the bottom, the Dirty Dozen’s own Kirk Jospeph returning to his traditional jazz roots? It’s almost too much to comprehend. Each musician in the Colossus Big Band is an individualist, instantly recognizable and able to call upon the tradition when necessary, while also drawing on over a century of music that has followed since Louis Armstrong left New Orleans for Chicago.

“This project is very near and dear to my heart and is something I’ve wanted to put together for a long time,” Braud wrote at the time of the sessions. “I feel so honored to have been able to get all these living legends into one room to record together, and I can’t wait to play with them all again. This session exemplified why I play this music - fellowship with the greatest alive.”

The music that follows does not require any further descriptions, nor does one have to be a historian to appreciate it; for fastest effect, you can stop reading here, play track one, and be prepared to have a good time (and you better be ready to dance). But if you’d like to go a little deeper, a few words are in order for the songs that make up Sing On.

Braud’s trumpet winks at the listeners immediately at the start of his original composition, “Royal St. Parade,” hinting at Louis Armstrong’s iconic “Cornet Chop Suey” entrance, before turning it into something new and different. In fact, that’s a good summary of this performance, with “Royal Street” joining “Bourbon Street” and “South Rampart Street” in the pantheon of New Orleans “Parade” songs.” The vibe is supremely relaxed--no one rushes in New Orleans--though special attention must be paid to Roderick Paulin’s extra funky outing.

Meghan Swartz’s gorgeous “When I Awaken” is the first of multiple dirges on Sing On. There are no solos, nor are any necessary with such beautiful playing from all involved, in particular Bruce Brackman’s crying clarinet at the end.

The album’s title track, “Sing On,” is an old hymn favored by drummer Paul Barbarin, who famously recorded it for Atlantic Records in 1955 with John Brunious Sr. on trumpet and Danny Barker on banjo; in fact, Braud pays tribute to his grandfather in the middle of the last chorus by quoting a blues-drenched line John Brunious loved to play on this number. In between, there’s some friendly back-and-forth between trombonists Lonzo and Klein, “two of my favorite musicians,” according to Braud; for a band with no chordal instruments, the trombones do a wonderful job throughout the album in outlining the harmonic structures of these songs.

With an evocative title like “Dirty Rice,” it’s hard to use any adjective other than “tasty” to describe this particular Braud original. Paulin’s up first, establishing a bluesy mood that is effortlessly carried over into Braud’s outing. Lonzo follows with some preaching of his own, spurred on by some truly earth-shaking drumming. Needing a helping of “Dirty Rice” of their own, the drummers make the most of a short solo spot before Braud leaps in for an exuberant finish.

Braud pays tribute to the intersection of “Rampart and Canal” with an incredibly catchy piece that really features nearly the entire ensemble splitting half-choruses. If you’re keeping score at home, Braud is up first, sounding very much like his uncle, followed by Brackman’s always surprising clarinet. The next chorus is split between a fluent Craig Klein and Wendell, the latter letting everyone know that he’s still the real deal and the source of so much inspiration! Freddie Lonzo grunts his way through his solo, backed by some effective riffs, leading Kevin Louis to enter with an earthy riff of his own before he takes flight (a reminder that the innovations of bebop are now 80 years old and part of the tradition, too). Braud returns to show the way out, leading with authority down to the emphatic last note.

“In Praise We Sing” is Braud’s contribution to the dirge tradition, playing stately lead while Brackman wails on top of the ensemble But watch out for the short and glorious “Celebration” reprise of the theme; when the band kicks into the extra chorus at the end, I felt my eyes well up with tears over the pure joy emanating from my speakers. This is just one reason why this tradition is so important to uphold--the world needs joy, and lots of it.

The title of Braud’s “Creole Cradle Song” conjures up a lullaby setting, but the drums immediately dispel that notion with a touch of what Jelly Roll Morton called the “Spanish tinge.” The horns deliver a particularly creamy rendering of Braud’s melody before the ensemble splits into two different bands for a chorus. Braud, Brackman, and Lonzo are up first before Louis, Klein, and Paulin take over at the bridge. A novel touch, highlighting just how much talent is contained in this particular group. Colossus, indeed….

It’s a treat to hear the good old, good one “Tiger Rag” get worked over for over five minutes, with lots of roaring to be heard in the ensembles. The trumpets step aside to let Klein, Brackman, and Lonzo take the solos, but once reassembled, the Colossus Brass Band takes no prisoners as they swing to a truly roaring finish.

Braud didn’t hide the inspiration behind his composition, “Go 'Head, Fred,” as Lonzo is the only soloist, blasting his way through an exciting stop time solo filled with his original twists and turns. There’s only one Freddie Lonzo!

Wendell Brunious handles melody duties on a relaxed reading of the spiritual “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” his phrasing and note choices the epitome of hip. In between the ensembles, Brackman solos on clarinet and Paulin solos on tenor, and the trombones once again come together in perfect harmony--great teamwork all around.

Gregg Stafford, who has mostly been heard on bass drum up to this point, finally gets some space to blow trumpet on a dirge of his choice, the perennial “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” which is offered again in a straight reading followed by a “celebration.” Stafford has probably performed this number thousands of times over his long career, but he still instills his heart and soul into it as if it was the first time he had ever played it.

Braud’s composition “If I Were Young Again” is a knockout, one that could totally become a modern-day standard, perhaps with the right set of lyrics. The melody alone is super catchy, and the band does it justice, with excellent solos from Brackman, Lonzo, and Louis (the latter quoting a familiar standard, “Exactly Like You”).

Wendell Brunious is back to play lead on “In His Care,” another memorable Meghan Swartz composition that has the feel of a right spiritual, with a bit of a hump in its back and a strut in its walk. After solos by Brunious, Paulin, and Klein, the closing ensemble reaches for the heavens with playing that can only be described as euphoric.

Like “Dirty Rice,” Braud’s “Sunday Struttin’” is perfectly titled, with a catchy melody that got stuck in my head for days (I didn’t complain). Wendell Brunious kicks off the solos, followed by a raucous Paulin (quoting Danny Barker’s “Chocko Mo Feendo Hey” towards the end) and an elastic Brackman. “I love the pairing of these two gentlemen,” Braud says of Paulin and Brackman. “They create something special when they play together.”

It’s not nice to play favorites but of all the traditional spirituals heard of Sing On, “By and By” might be the tops for me. The instantly identifiable soloists are Lonzo, Stafford, Brackman, and Paulin, but it’s the final choruses that raised the hair on top of my head. When Kirk Joseph switches to playing 4/4 time on his sousaphone--watch out! Music like this makes me grateful to be alive.

Braud is quick to not let the party atmosphere get too carried away, bringing us back to reality with his sobering “When the Burden is Lifted.” This one is a feature for Bruce Brackman’s haunting clarinet; no one has played the instrument like this since John Casimir’s chilling work with the Young Tuxedo Brass Band.

There’s only one way to conclude Sing On, with a crowd-pleasing rendering of the national anthem of New Orleans, “When the Saints Go Marching In.” Braud plays lead, but generously allows space for Stafford, Lonzo, and Brackman to make personal statements of their own. Braud shows the way out, once again paying tribute to those who came before him with playing that conjures up the sounds of Louis Armstrong, John Brunious Sr., and Wendell Brunious, all fused together in Braud’s original, captivating style.

When word of the Colossus Brass Band first reached social media, it almost seemed too good to be true. The results have more than lived up to the hype. As the history of New Orleans jazz continues to be written and rewritten, the Colossus Brass Band will take its rightful place in the pantheon next to all who came before and will continue to pave the way for all who will follow. The tradition will continue to sing on, and the song will never end.

Ricky Riccardi

Ricky Riccardi is the Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum, author of three critically acclaimed biographies of Armstrong, and winner of two GRAMMY Awards for “Best Liner Notes.”